On November 17, 1840, John Quincy Adams, sixth President of the United States, and then serving in Congress, visited thirty-six African men being held outside of New Haven, Connecticut.  The Africans who had mutinied on a Spanish slave ship were being tried for piracy and murder on the high seas. Adams's involvement as a former President and perhaps even more significantly as the son of one of the nation's most important Founding Fathers marked an important point in United States history. Here at last was an almost direct connection between the cause of antislavery and the nation's Revolutionary principles of liberty and equality.

The Africans who had mutinied on a Spanish slave ship were being tried for piracy and murder on the high seas. Adams's involvement as a former President and perhaps even more significantly as the son of one of the nation's most important Founding Fathers marked an important point in United States history. Here at last was an almost direct connection between the cause of antislavery and the nation's Revolutionary principles of liberty and equality.

The thirty-six Africans had been among five or six hundred purchased by a Portuguese slave trader in April 1839. They were shipped to Havana, Cuba, then a Spanish colony. Although slavery was legal in many countries, the international slave trade had been banned by laws and treaties in nations such as Great Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United States. Nevertheless, a prosperous slave trade continued, and few traders were caught.

The Africans were landed near Havana and sold openly in the slave market. Fifty-two members of the Mendi tribe, from present-day Nigeria, who survived the horrors of the Middle Passage were sold to Jos‚ Ruiz and Pedro Montez, two Cubans who planned to sell them to a Cuban sugar plantation. The Mendians were given Spanish names and designated as "black ladinos," indicating that they had lived in the country long enough to know the language and customs. Utilizing the deception that the Mendians had been long-term slaves in Cuba, Ruiz and Montez placed them on board the schooner Amistad, and set sail for a port down the Cuban coast on June 28, 1839.

Although slavery was legal in many countries, the international slave trade had been banned by laws and treaties in nations such as Great Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United States. Nevertheless, a prosperous slave trade continued, and few traders were caught.

The Africans were landed near Havana and sold openly in the slave market. Fifty-two members of the Mendi tribe, from present-day Nigeria, who survived the horrors of the Middle Passage were sold to Jos‚ Ruiz and Pedro Montez, two Cubans who planned to sell them to a Cuban sugar plantation. The Mendians were given Spanish names and designated as "black ladinos," indicating that they had lived in the country long enough to know the language and customs. Utilizing the deception that the Mendians had been long-term slaves in Cuba, Ruiz and Montez placed them on board the schooner Amistad, and set sail for a port down the Cuban coast on June 28, 1839.

On the fourth night out, the Mendians broke free of their chains, seized machetes, and waited until morning. At dawn, they attacked the captain and his three-man crew. Their leader, Singbe-Pi‚h, given the Spanish name Cinque, killed the captain; the cook was also killed. Two members of the crew escaped in the ship's boat; the cabin boy, an actual ladino, was not harmed.  The two Cuban slavers, spared on the promise that they would take the vessel back to Africa, steered east to Africa by day, but turned the ship toward the United States by night, hoping to make some friendly southern port. On August 26, the Amistad, its provisions exhausted, was apprehended off Long Island by a U.S. Coastal Survey brig and taken to New London, Connecticut. Ruiz and Montez immediately denounced the Mendians as revolted slaves, pirates, and murderers, and claimed them as their property. The Mendians, who did not speak English or Spanish and thus could not communicate with anyone, were brought before a federal judge, who set a trial date. The Spanish ambassador became involved, demanding that President Martin Van Buren return the ship and the Mendians to Ruiz and Montez, and that the whole matter be dealt with under Spanish law, as treaty obligations stipulated. Van Buren agreed, preferring to return the Mendians and in so doing not alienate his southern proslavery support, but the matter had already been placed under court jurisdiction.

The two Cuban slavers, spared on the promise that they would take the vessel back to Africa, steered east to Africa by day, but turned the ship toward the United States by night, hoping to make some friendly southern port. On August 26, the Amistad, its provisions exhausted, was apprehended off Long Island by a U.S. Coastal Survey brig and taken to New London, Connecticut. Ruiz and Montez immediately denounced the Mendians as revolted slaves, pirates, and murderers, and claimed them as their property. The Mendians, who did not speak English or Spanish and thus could not communicate with anyone, were brought before a federal judge, who set a trial date. The Spanish ambassador became involved, demanding that President Martin Van Buren return the ship and the Mendians to Ruiz and Montez, and that the whole matter be dealt with under Spanish law, as treaty obligations stipulated. Van Buren agreed, preferring to return the Mendians and in so doing not alienate his southern proslavery support, but the matter had already been placed under court jurisdiction.

At this point, three prominent abolitionists intervened: Lewis Tappan, a merchant and industrialist who had raised funds to defend and care for the Mendians; the Reverend Joshua Leavitt, editor of the antislavery journal, Emancipator; and Simeon S. Jocelyn, an engraver active in the antislavery movement.After obtaining legal counsel, the abolitionists found a translator to take testimony from the Mendians; they learned they had been kidnapped, were in Cuba only a few days, and thus were not ladinos. The Mendians' testimony became the basis of the defense's case.

the Reverend Joshua Leavitt, editor of the antislavery journal, Emancipator; and Simeon S. Jocelyn, an engraver active in the antislavery movement.After obtaining legal counsel, the abolitionists found a translator to take testimony from the Mendians; they learned they had been kidnapped, were in Cuba only a few days, and thus were not ladinos. The Mendians' testimony became the basis of the defense's case.

On January 7, 1840, the Mendians' trial began in the District Court in Hartford, Connecticut. Tappan, aided by a British commissioner stationed in Havana to help suppress the illegal slave trade, uncovered evidence to support the Mendians' story: the documents establishing them as ladinos were forged. The judge, persuaded by this evidence, concluded that even under Spanish law, the Mendians were free men, and ordered President Van Buren to have them transported back to Africa. Interestingly, the court also determined that the cabin boy the ladino was a slave, the property of Ruiz and Montez, and should be returned to his owners. With the aid of the abolitionists, however, he fled to New York, and to freedom.

Van Buren, furious and worried that this case would damage his standing in the South, ordered the government's lawyers to appeal the case to the Supreme Court.  For their part, the abolitionists determined to add an eminent lawyer to augment the defense team. After being turned down by leading trial lawyers in Boston, Tappan then approached John Quincy Adams, who after some hesitation agreed. Adams was merely a lukewarm supporter of abolitionism and had even angered Tappan by his refusal to support the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. He had become interested in the Amistad case when it was tried in the District Court, but Tappan had rejected his initial offer of assistance.

The case went before the Supreme Court on February 22, 1841; Adams considered the date of George Washington's birthday a good omen. Adams's argument, extending over two days and lasting seven hours, centered on what he considered to be the cornerstone of Anglo-American rights and liberties, the principle of habeas corpus. By Spain's own laws, he argued, the Mendians were illegally enslaved. If the President could hand over free men on the demand of a foreign government, how could any man, woman, and child in the United States ever be sure of their "blessing of freedom"? The Court, with one dissent, agreed. However, while the Court's decision was a moral victory for the abolitionist cause, it did not address either the legality of slavery or the status of runaway slaves in America.

For their part, the abolitionists determined to add an eminent lawyer to augment the defense team. After being turned down by leading trial lawyers in Boston, Tappan then approached John Quincy Adams, who after some hesitation agreed. Adams was merely a lukewarm supporter of abolitionism and had even angered Tappan by his refusal to support the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. He had become interested in the Amistad case when it was tried in the District Court, but Tappan had rejected his initial offer of assistance.

The case went before the Supreme Court on February 22, 1841; Adams considered the date of George Washington's birthday a good omen. Adams's argument, extending over two days and lasting seven hours, centered on what he considered to be the cornerstone of Anglo-American rights and liberties, the principle of habeas corpus. By Spain's own laws, he argued, the Mendians were illegally enslaved. If the President could hand over free men on the demand of a foreign government, how could any man, woman, and child in the United States ever be sure of their "blessing of freedom"? The Court, with one dissent, agreed. However, while the Court's decision was a moral victory for the abolitionist cause, it did not address either the legality of slavery or the status of runaway slaves in America.

By the time the Court rendered its decision, John Tyler, a southern proslavery Whig, was President; he refused to provide a warship for the Mendians' return. In December 1841, Tappan and his fellow abolitionists provided a ship and missionaries who would accompany the Africans home. Cinque returned to become a chief of his people. While stories persist that he became a slave trader, there is no documentation to support this claim. In 1878, near death, Cinque returned to the mission and died a Christian. One of the Amistad Mendians, Margru, served with the missionaries.

While the Amistad case cannot be viewed as a legal or political turning point in the struggle against slavery in the United States, it was a victory for the abolitionists, providing a further demarcation of the forces for and against slavery. The Amistad episode was a signal event in a course that would ineluctably lead to the irrepressible conflict of the Civil War, almost two decades in the future.

By the time the Court rendered its decision, John Tyler, a southern proslavery Whig, was President; he refused to provide a warship for the Mendians' return. In December 1841, Tappan and his fellow abolitionists provided a ship and missionaries who would accompany the Africans home. Cinque returned to become a chief of his people. While stories persist that he became a slave trader, there is no documentation to support this claim. In 1878, near death, Cinque returned to the mission and died a Christian. One of the Amistad Mendians, Margru, served with the missionaries.

While the Amistad case cannot be viewed as a legal or political turning point in the struggle against slavery in the United States, it was a victory for the abolitionists, providing a further demarcation of the forces for and against slavery. The Amistad episode was a signal event in a course that would ineluctably lead to the irrepressible conflict of the Civil War, almost two decades in the future.

The National Portrait Gallery's permanent collection contains images of several of the participants in the Amistad episode. The portraits listed below follow their order of appearance in the text:

John Quincy Adams,1767-1848

Sixth President of the United States

George Caleb Bingham, 1811-1879

Oil on canvas, 1793

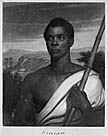

Cinque,1817?-1879?

Insurrectionist and leader of the Mendians.

John Sartain (1808-1897), after Nathaniel Jocelyn

Mezzotint, c. 1840

John Caldwell Calhoun, 1782-1850

Statesman and leading proslavery senator. Authored resolutions calling for the return of the Africans to Spain.

George Peter Alexander Healy (1813-1894)

Oil on canvas, c. 1846

James A. Thome, 1809-1873

Abolitionist and author of Emancipation in the West Indes

Nathaniel Jocelyn (1796-1881), artist and brother of Simeon S. Jocelyn who aided the Mendians.

Oil on canvas, 1840

Martin Van Buren, 1782-1862

Eighth President of the United States

Mathew Brady (1823-1896)

Daguerreotype, c. 1856

Joseph Story, 1779-1845

Supreme Court Justice for the Amistad trial.

Chester Harding (1792-1866)

Oil on canvas, 1827