The Night I Met Lenny

I have only been wowed by a person three times in my life, despite having met and known, thus far, hundreds of major and minor celebrities in the arts, in show business, in politics, and in civil rights. All three of these particular moments occurred when I was in my twenties when I believe I was allowed, even expected, to be impressed: in chronological order, the first time was when I danced with Vice President Hubert Humphrey at a private dinner party hosted by Carl Rowen, a journalist who was himself a celebrity in his field; the second time, was when I met Martin Luther King at Airlie House, a conference center used frequently by non-profit organizations on the eastern seaboard (I was there for an Urban League retreat and he for an SCLC conference), and the third time was when I was a dinner guest at a seated dinner party of ten where the guest of honor was Leonard Bernstein (BURN’styne). This is the centennial year of Leonard Bernstein’s birth: he was born on August 25, 1918 and was, according to sources, one of the first conductors born and educated in the United States who would achieve world-wide acclaim.

As I remember that evening, I now regret never consistently having kept a journal. Having been blessed with what was then a prodigious memory, I suppose I thought I would remember forever the details of such an auspicious occasion. (What did I know at twenty-six?) I can tell you now that I cannot remember a single other guest at the dinner – not even the name of the hostess (names go first), although I can see her face clearly. All I can remember is the fact of the presence of Leonard Bernstein, the single most charismatic man I have ever met in my entire life. I was dazzled. He was, after all, the composer of West Side Story, one of the few musicals I really love. (I prefer opera.) In possession of the “wow” factor to the nth degree, though only 5’7” to my 5’6”, Leonard Bernstein, nevertheless, left me with the impression that he was six feet tall (or 5’10’’ at the very least).

The conversation that evening was what was to be expected at a Washington dinner party: politics, of course, civil rights, naturally, and his feelings about Washington, in particular. He had had a difficult time returning to the White House, he said, where he’d visited several times over the years. In a later interview, he expressed that the assassination of President Kennedy, with whom he had been friends, had left him so grief-stricken, that he turned away from looking at the White House whenever he passed.

I did conclude from the discussions during the evening, that he was fiercely liberal. Later I learned of his involvement in what were called “leftist” activities in the 1940s and that he had even been blacklisted by the State Department, though it had never significantly affected his career. In later years, after a satirical essay by Tom Wolfe entitled Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s for New York magazine, his social activist positions were often identified derisively as “radical chic.” The “party” in the title, referred to an event hosted by Bernstein and his wife, Felicia, in their attempt to raise awareness and money for the defense of several Black Panthers against a variety of charges. None of that surprised me, since one of my closest friends from college had worked tirelessly in New York City to support the Black Panther breakfast program, a project that fed impoverished school children. The knowledge of his involvement only made me love him more. Perhaps what a Washington Post critic saw in his music as too emotional, too overwrought is simply evidence of a man who cared deeply and invested that caring in his art.

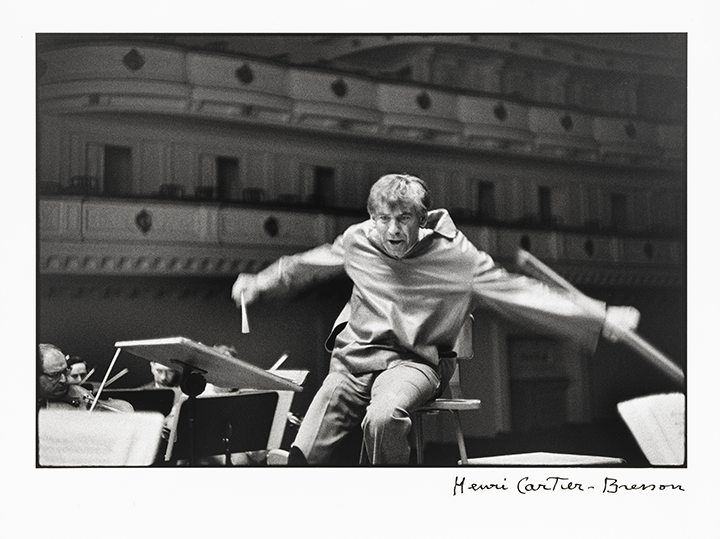

In retrospect, despite his many awards and accolades which included several Tonys and many Grammys, I was most impressed with his work as a music educator. Perhaps because both of my parents were teachers, I have great respect for education in general and especially for arts education and mourn the sacrifice of the arts in today’s education budgets. So I appreciated his Bernstein Young People’s Concerts most. He produced 53 of those televised music appreciation programs for young people, the success of which depended, it seems to me, as much on his charisma in communication as his prowess as an artist.

His career in music spanned a fifty year period from 1940 to 1990 as composer, conductor, author, music educator, and pianist and was celebrated and rewarded all over the world. Lately the emphasis in print on his personal life and his sometimes idiosyncratic behavior seems unnecessary and, perhaps, even prurient. Social media appears to have succeeded in whetting our collective appetites for the personal and often irrelevant details of existence. My conclusion about him in all of this is to say, I liked the man and I loved his music. Rest in peace, Lenny Bernstein. Your contributions to American arts is eternal.