The Tragedy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory

By late afternoon on March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City was ablaze, and after thirty minutes, it became one of the largest industrial disasters recorded in U.S. history. The fire forever changed the course of industrial practices and conditions within the United States.

Here is what happened: a small fire broke out on the eighth floor and quickly spread to the remaining levels (9th and 10th) of the Asch Building located in Greenwich Village. Normal escape routes, such as the front doors, were locked, resulting in the entrapment of the employees, who were mostly young women. Many of them tried to escape by the elevator (10 people at a time), by the stairwell, or by the fire escape. But soon, these routes either collapsed from overcrowding or were blocked by billowing flames. Desperate to get out, employees began jumping from the upper-story windows or from the open elevator shaft. Unfortunately, many remained trapped on the ninth floor; 146 victims perished.

In its aftermath, the Triangle fire inspired a great campaign of workplace reform. About thirty separate laws were passed, including those regulating the minimum wage and working conditions. Additionally, the New York City commissioner began factory inspections and concluded that hundreds of the City’s factories were unsafe. But, it didn’t stop there! The fire had so overwhelmed the city with grief that many citizens – men and women – were inspired to take action as well. Nearly 400,000 people gathered for the mass funeral of the victims, completely filling the streets of New York. Accounts of the funeral march describe how there was no music, nor any sound at all –the marchers wanted the silence of their protest to be heard.

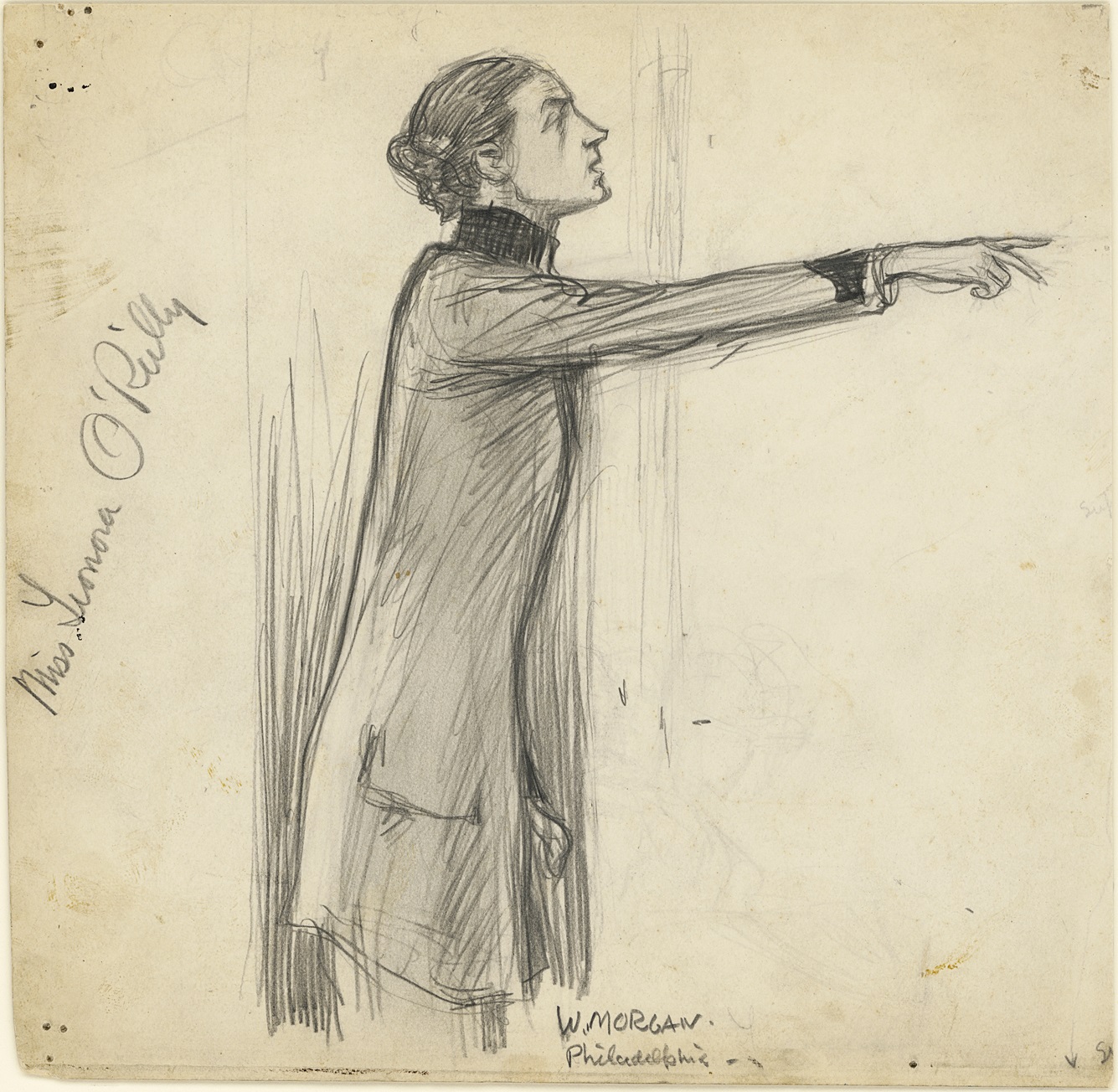

How did it come to this? The Triangle factory itself had been no stranger to demonstration. In fact, in September of 1909, four hundred factory employees took part in a spontaneous walkout to challenge the factory’s working conditions. Later in November, union leaders and workers gathered for a strike meeting in the Great Hall of The Cooper Union. Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), called for all Triangle factory employees to stage another walkout. After Gompers and other speakers finished addressing the crowd, Clara Lemlich, a garment worker and member of the ILGWU, took to the podium. She urged workers of all factories to protest together in one “general strike”, now known as the New York Shirtwaist Strike of 1909. The work of Gompers, Lemlich, and later the tragedy of the fire would go on to inspire many other activists, including Leonora O’ Reilly, Frances Perkins, Anne Morgan and Alva Belmont.

It is hard to read the firsthand accounts of those that survived the Triangle factory fire because of the horror that they relate. How different would our lives be today without the persistent efforts of those that challenged these dangerous practices in factories and in the workplace?